Early Minnesota Artists

Minnesota Natives and Immigrant Artists

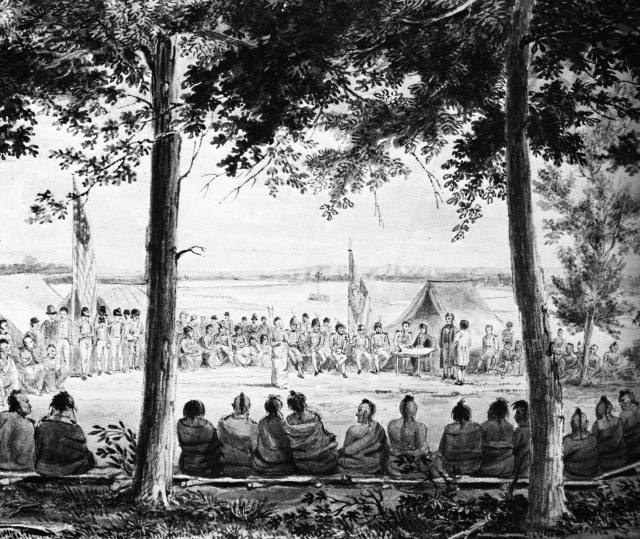

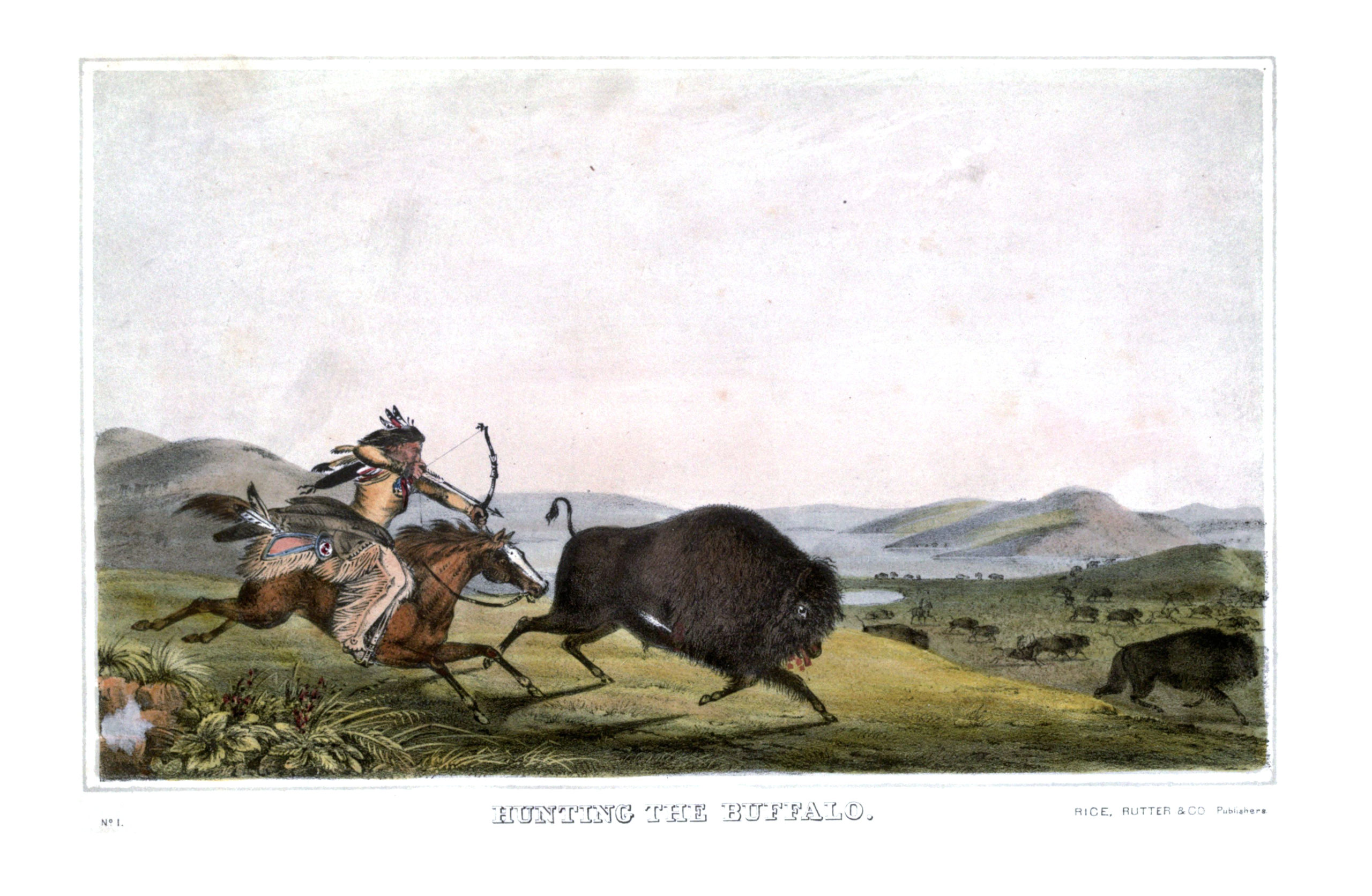

The humble beginnings of art in Minnesota involved interactions between several particular groupings of people. This was apparent in why individuals came to the area, where they stayed, and what they portrayed. The earliest anglo (that is, non-native) creators of art in Minnesota were members of traveling expeditions to the territory between 1839 to 1850, who had little to no formal artistic training. From the east, they were traveling on expeditions out into the west. The first known artist to visually document the area and its inhabitants was Samuel Seymour (b. 1796). Like him, many artists played a dominant role in shaping how native Indians were portrayed in art, and thus also how the inhabitants were viewed by newcomers in general (see Pawnees below). Peter Rindisbacher (b. 1806) was a very influential artist in portraying Native Indian inhabitants as skilled and daring buffalo hunters (see Hunting the Buffalo below).

Samuel Seymour, “Pawnees in a parley with Major Stephen Long’s Expedition at Council Bluffs, Iowa” 1819, from original watercolor

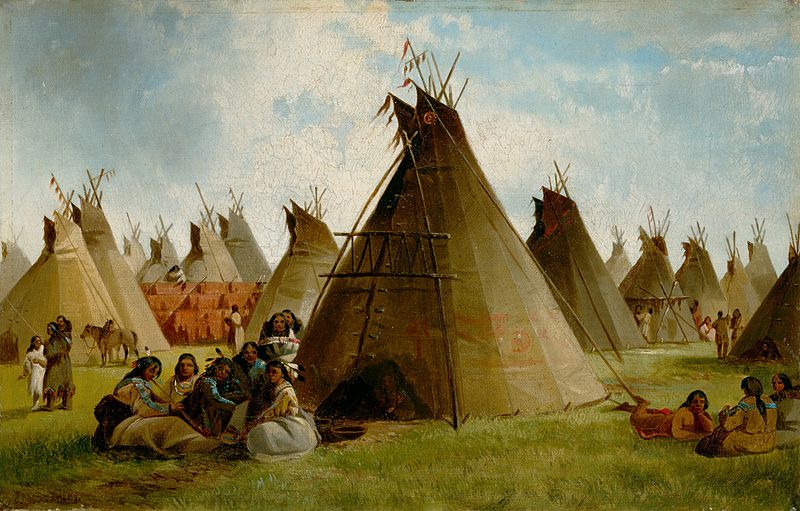

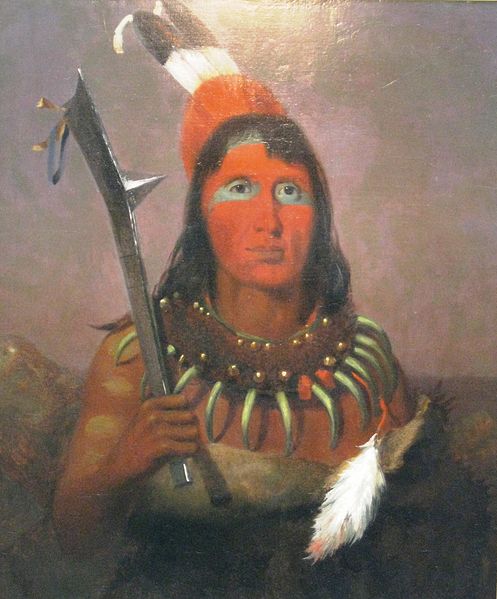

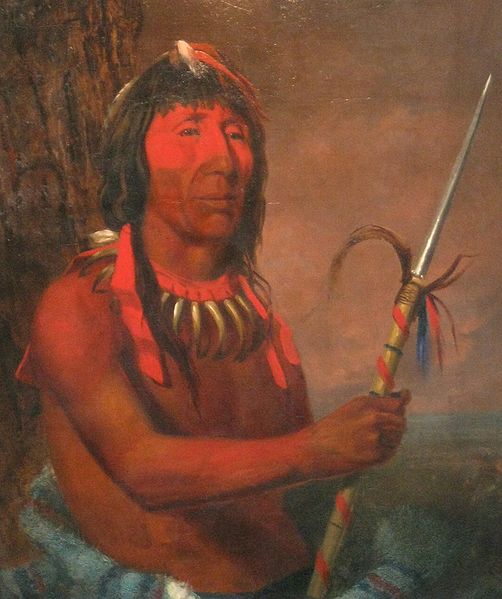

The well-known artist George Catlin (b. 1796) travelled with, painted, and wrote about the Indians “to rescue from a hasty oblivion a truly noble and lofty race.” Contrasted with Catlin’s portraits of white anglos, his portraits of natives were much freer, with sweeping brushstrokes. John Mix Stanley’s (b. 1814) work was published in portfolio reproductions, popularizing in eastern America what the west looked like. Examples of his work are Prairie Indian Encampment and On the Warpath (pictured below), direct compositions that were carefully designed. George Catlin established an Indian gallery of art, which inspired Charles Deas (b. 1818) to pursue travel to the Midwest. There Deas painted the lands and portraits of the Sioux. Members of the Sioux resisted posing for portraits because they did not trust representational art, fearing that created likenesses would “take away from their bodies,” by physically diminishing or even destroying them. A brave medicine man’s agreement to pose paved the way for other sitters. Some portraits created by Deas are shown below.

John Mix Stanley, “Prairie Indian Encampment” c.1870, oil on canvas, 23 inches x 36 inches, Detroit Institute of Arts

John Mix Stanley, “On the Warpath” 1872, chromolithograph, 22.4 inches x 30.4 inches, Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth, Texas

(Left): Charles Deas “Wa-kon-cha-hi-re-ga” 1840, oil on canvas, 34 inches x 50 inches, St. Louis Mercantile Library, University of Missouri. (Center): Charles Deas, “Winnebago [Man] with Bear Claw Necklace and Gunstock Club” 1840, photograph of original oil painting. (Right): Charles Deas, “Winnebago [Man] with Bear Claw Necklace” 1840, photograph of original oil painting, St Louis Mercantile Library, University of Missouri.

The earliest white artists to work in Minnesota, before it was considered a state in the union, would stay at the first hub that was Fort Snelling, or on reservations. Some explorers (such as Albert Bierstadt, b. 1830, painting below) were part of expeditions to create maps for routes. They depicted the same subjects: the land, portraits, and daily activity of the inhabitants. These artists jointly witnessed the beauty of the culture before them and wished to capture that truth onto their papers and canvases.

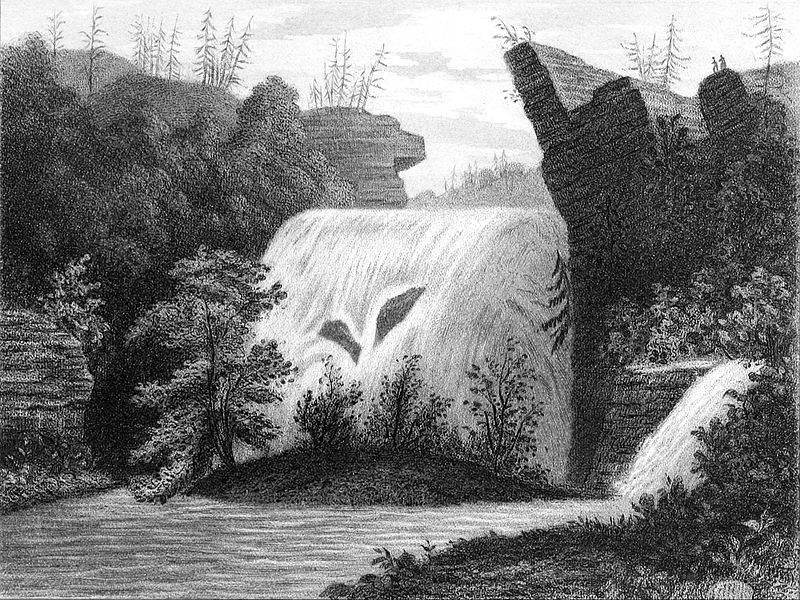

Aside from explorer artists, there were also artist soldiers camped at Fort Snelling, settler artists that were calling newly found land their home, and tourists to newly settled spots. In the 1830s there were also panorama painters that constructed entertainment; they specialized in creating long canvas scrolls for public spectacles with paid admission that included live music, commentary, and acrobats. At least one man in the state was a commercial artist. Edwin Whitefield (b. 1816) created lithographs based on on-site watercolors, which were distributed widely by land promoters as pictorial advertisements to attract settlers to new areas.

Edwin Whitefield, “Ithaca Falls” 1855. Engraving by J. C. McRae based on drawing by Edwin Whitefield. Published in “The Rose of Sharon,” 1855.

Frontier community folk artists had no formal art training and few to zero examples of art. In contrast, soldier artists were more inclined to receive training. The often-noted captain Seth Eastman (b. 1808) studied at West Point. He was part of the Hudson River School of American painting, comprised of artists that painted outdoors in a shared reverence for nature. They were the first plein air, or outdoor, painters in the nineteenth century. The range of earliest artists to work in the state included explorers, soldiers, panorama, commercial, settlers, and frontier folk artists. These artists moved through Minnesota territory and the midwest, conceiving and directly supplying the initial image of the American frontier.

Recent Comments